Each month the Carnegie Museum of the Arts Hillman Photography Initiative invites response to an interesting, sometime provocative image.

The image for March, 2015 is Sara Cwynar’s Girl from Contact Sheet 2 (Darkroom Manuals), 2013, accompanied by this question, “How has photography’s shift affected you? This month’s photo, Girl from Contact Sheet 2 (Darkroom Manuals), shows an uncertain history of manipulation or data loss. Look closely. Its digital blur suggests what happens when photography straddles two worlds. How has the dramatic shift from print to digital impacted you? What does this image say about the gains and losses of this transition? Respond to this picture and our questions with text, photos, videos, or audio files, and we’ll feature your response on our website.”

Sara Cwynar’s “Girl from Contact Sheet 2 (Darkroom Manuals),” 2013. Courtesy the artist and Foxy Production, NY

My immediate, almost visceral, non-verbal response was to post a copy of The Wave of the Future, a 1983 poster that struck me at the time as a brilliant depiction of the digital revolution about to sweep society.

The poster pictures Katsushika Hokusai’s 19th-century Great Wave off Kanagawa, its surf breaking into pixels that, in turn, transform into a digital map of an even larger wave. The image reads like a historical scroll; it was prescient.

Judy Kirpich, a creator of The Wave of the Future tells the story of how it came to be. Ironically, the startlingly perceptive vision of the future of digital imaging was actually produced entirely by hand. Digital image-mapping was prohibitively expensive in 1981; there was no Photoshop or Illustrator. A team of designers and illustrators spent days creating six separate overlays, hand-coloring each little square on acetates spread over the original lithograph and inking in each line of the digital wave.

The poster was published right around the time I acquired my first personal computer, a Kaypro “luggable” that had a nine-inch, green monochrome screen whose display relied entirely on keyboard (ASCII) characters. While a clever programmer could do some amazing things with such a palette, it would be almost a decade before I would have a computer with a truly graphical interface. However, I had gotten hints of the graphic potential of digital imaging a few years earlier.

In the 1960s and ’70s, Bell Labs was doing research into human perception, computer vision and graphics that underlies today’s high-definition computer and video graphics. In 1973, Leon Harmon, a leading researcher of mental/neural processing of what we see, published “The Recognition of Faces,” the cover story in the November issue of Scientific American.

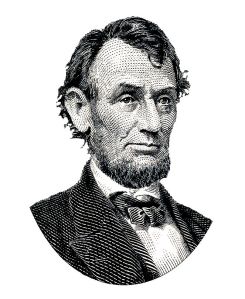

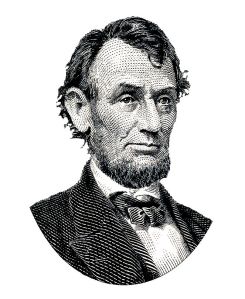

In his research, Harmon overlaid a 16 x 16 grid of squares on the portrait of Lincoln etched on the US five-dollar bill, the uniform color of each square averaging the color of all the points within it.

The result is an image that up-close resembles a black and white Piet Mondrian print, but from across the room looks like a blurry image of Honest Abe. It went as “viral” as an image could in those analog days.

Within a year, Salvador Dali incorporated not only Harmon’s photo-mosaic technique but the Lincoln image itself into a painting of his wife—Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea which at a distance of 20 meters is transformed into the portrait of Abraham Lincoln (Homage to Rothko).

Lincoln in Dalivision

Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea, which at a distance of 20 meters is transformed into the portrait of Abraham Lincoln (Homage to Rothko)

The painting was displayed at the Guggenheim in New York during the US Bicentennial in 1976. That same year, Dali published a slightly different version of the image as a lithograph edition of 1240: Lincoln in Dalivision. Within three years, both Harmon’s and Dali’s images had gone around the world.

These analog images illustrate a photo-mosaic presentation of visual information that would become fundamental to digital graphics—from arrangement of photon sensors and interpretation of their signals in our cameras to the pixels of color on HD TVs, computer screens and patterns of ink spots printed on photo paper.

To be continued…

You must be logged in to post a comment.